Readers of mine might have gotten the idea that I incline to dystopian thinking or outright cynicism over utopian optimism.

They would be right, and I’m not sorry.

The idea that we’re currently living in a cyberpunk dystopia has been around long enough1 long enough to have sparked at least one widespread online backlash, which I found unconvincing. (It boiled down to “you shouldn’t care how accurately that worldview matches real-world events, because that makes it harder for me to sell you on my political program.”)

But even beneath that, at the bedrock level of basic principle, I find utopia unconvincing.

You may have heard the one about the blind men and the elephant – that story has been retold, with minor variations, for millenia. It’s often used to illustrate how our grasp of truth can be accurate as far as it goes but still grievously limited. Now let’s apply that to the subject at hand…

A utopian transformation of society can do good in proportion to how well its planners understand society; every mistake and blind spot of theirs will lead to unintended harm.2 And society – even if we define it as merely “the sum total of human interactions,” as I sometimes do, and not all human activity – is unknowable. It’s too complex, too big, for anyone to understand more than a fraction of it, at best. Therefore, harm is inevitable.

A utopian vision can never admit this.

I’m going to use solarpunk as an example, only because it’s a current utopian movement (or art style, or subculture, or whatever it is) that has come up a lot for me recently, from a piece on “solarpunk” car design from earlier this year that popped up in my daily oldest tiddlers last week to multiple Minecraft videos like this one,

Let’s start with that Minecraft video. I’m willing to let a few things slide – like the apparently superfluous aqueduct, the artificial patch of hilly green parkland on a platform over a cargo pier (to the probable detriment of both), and the artistically shaped artificial islands (cough, Dubai, cough) – because it’s a Minecraft build, not a detailed design proposal. Instead, I’ll start with the monorail.

Monorail (or some other kind of mass transit) is a defensible idea. Elevating the tracks makes them more aesthetic, at least from a distance, and letting trees grow beside the tracks adds a green veneer to the whole project… at least until a tree’s growing roots shift a section of track and derail a train right into the side of a nearby apartment building. But until then, it looks leafy and graceful, which is more important.

Or:

The Delta District, located on the east side of the island, contains the oldest neighborhood in the city. To use the land more efficiently, buildings were constructed so that their roofs formed one large green roof for community parks, gardens, and solar panels.

Let’s assume that the level of architectural micromanagement needed to make this happen doesn’t come from citywide building codes, because the city has a variety of different (though often equally controlled) building styles. Maybe each neighborhood has its own homwoener association with its own building code… and for those of you who need a minute to control your blood pressure or nausea at the mention of HOAs, I’m done with the subject already, and you can come back whenever you feel able.

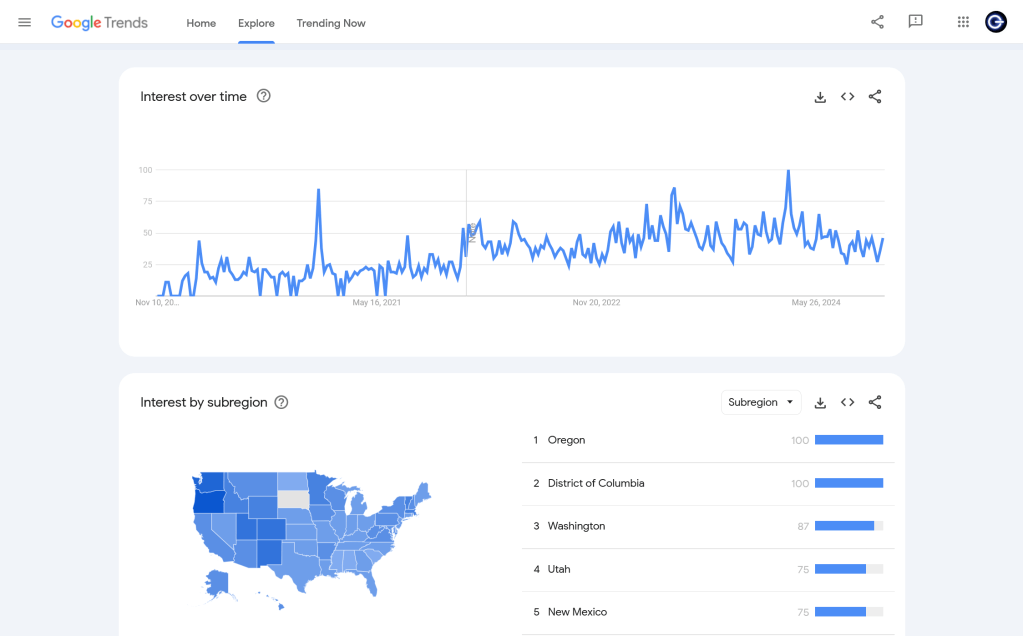

Some of my posts are conceived well in advance of my first draft. This one wasn’t, though, so I haven’t been counting how many times I’ve seen solarpunk called “an emerging trend” that’s “been capturing a lot of attention recently“, but they’ve been numerous enough to have left at least a residual impression on me.

The rise in solarpunk interest doesn’t look all that steep from here, though:

I found the “interest by subregion” part informative. Two of the top three interested areas are Oregon and Washington state, possibly because of Solarpunk Portland, a seemingly at least semi-organized effort to turn Portland, Oregon into a solarpunk utopia.

The second-highest interested area? D.C.

Enough Minecraft. On to an intended real-life example: Solarpunk Portland’s proposed “sidewalk system,” a set of motorized roller conveyor belts for moving “people and light cargo at highway speeds without requiring two-ton vehicles to carry them”, thus saving energy.

The devil’s in the details, as usual.

The 60 mph “express lane” has seats, so you don’t have to try to keep standing upright on rollers that are pushing you along at 60 mph, and “blowers are provided” so you don’t have to eat a 60 mph headwind. Whether you can stand on the rollers in the 20 mph “intermediate lane,” with those blowers generating a relative 40 mph tailwind, is left unexamined.

And so is the energy savings – sure, car use is reduced, but those rollers have to move 24/7 with enough force to push a truckload of cargo.

How do you move cargo onto and off the “sidewalk” in the first place, anyway? The wheels of hand trucks and the like would get hung up on the rollers. And shoelaces would have to be banned….

We’re not supposed to think, though. That’s the real problem. (And here’s where my distaste for this shit starts to boil over.)

Utopia usually isn’t about thinking. It isn’t about figuring out what changes would improve the world and how best to achieve them. It isn’t even about letting our self-appointed betters think of them, because if I could poke that many holes in a seriously intended policy proposal in a matter of minutesr,3 then they haven’t thought it through either and can’t be bothered to have pretended to.

There is the occasional counterexample, the odd literary thought experiment from which some kernel of insight can be gleaned, or at least some entertainment value, but that’s in art, and only in some art.

The rest of the time, utopia is hype. It’s a shiny wrapper around whatever project – “smart” cities, tax subsidies, etc. – someone wants to sell at the moment.

Remember how interested D.C. was in solarpunk? This is why.

The only criticism of Solarpunk Portland I could immediately find was that Portland is demographically very white, and therefore the project’s central planners will inevitably also be mostly white. This writer was still broadly in favor of Solarpunk Portland, as one might expect from a co-editor of Solarpunk Magazine, but it has nothing obvious to do with what the political class would rather have us fight over right now.

Oh, no. Two brands of political marketing don’t have enough synergy.

Contrast this with a real humanistic cultural movement:

As a guy of a certain age with anti-establishment feelings, I have some respect for the counterculture of my parents’ generation. You can argue about how much good they did long-term, but you can’t deny they tried.

“Turn on, tune in, drop out” was the way they put it. In other words:

- Become more conscious, more aware

- Become more socially adept, or at least more open to the possibility of connection

- Become less attached to convention and less prone to conformity

Leary fiddled with the phrase in later years, but the underlying idea stayed the same.

I suspect that the average utopian proponent would rather we did the opposite.

This list is now some years out of date. Ask a Tesla antifan about number 27, for example.

I’m assuming, for the sake of argument, that our hypothetical utopian planners don’t intend harm. I’m sure some readers will have already thought of historical examples of central planners who tried to achieve their perfect society by eliminating “undesirable” people, or some plan for sweeping societal change that just coioncidentally concentrated more of that society’s wealth and power in its planners’ hands.

I didn’t think of the sidewalk system’s inevitable noise pollution until maybe an hour later, after I’d rewatched that Minecraft video.

Featured image by Brian Kungu on Unsplash

LikeLike